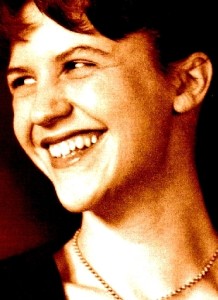

Last week, on October 27, was 83 anniversary of Sylvia’s birth. Pulitzer Prize-winning author who left in the wake of her own disaster, a legacy of lyrics that join alarming force and amazing creativity. With the brutally frank self-exposure and emotional immediacy, Plath’s poems, from “Lady Lazarus” to “Daddy,” have had a continuing impact on contemporary verse.

Her novel ‘Bell Jar’ was published in January 1963 under Plath’s chosen pseudonym Victoria Lucas.

Plath can be analysed from various perspectives as feminist and feminine, mythological and political, an English Romantic and an American Modernist.

Here is her a well-known poetry ‘Daddy‘

You do not do, you do not do

Any more, black shoe

In which I have lived like a foot

For thirty years, poor and white,

Barely daring to breathe or Achoo.

Daddy, I have had to kill you.

You died before I had time—-

Marble-heavy, a bag full of God,

Ghastly statue with one gray toe

Big as a Frisco seal

And a head in the freakish Atlantic

Where it pours bean green over blue

In the waters off the beautiful Nauset.

I used to pray to recover you.

Ach, du.

In the German tongue, in the Polish town

Scraped flat by the roller

Of wars, wars, wars.

But the name of the town is common.

My Polack friend

Says there are a dozen or two.

So I never could tell where you

Put your foot, your root,

I never could talk to you.

The tongue stuck in my jaw.

It stuck in a barb wire snare.

Ich, ich, ich, ich,

I could hardly speak.

I thought every German was you.

And the language obscene

An engine, an engine,

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

I began to talk like a Jew.

I think I may well be a Jew.

The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna

Are not very pure or true.

With my gypsy ancestress and my weird luck

And my Taroc pack and my Taroc pack

I may be a bit of a Jew.

I have always been scared of you,

With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo.

And your neat mustache

And your Aryan eye, bright blue.

Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You——

Not God but a swastika

So black no sky could squeak through.

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

You stand at the blackboard, daddy,

In the picture I have of you,

A cleft in your chin instead of your foot

But no less a devil for that, no not

Any less the black man who

Bit my pretty red heart in two.

I was ten when they buried you.

At twenty I tried to die

And get back, back, back to you.

I thought even the bones would do.

But they pulled me out of the sack,

And they stuck me together with glue.

And then I knew what to do.

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf look

And a love of the rack and the screw.

And I said I do, I do.

So daddy, I’m finally through.

The black telephone’s off at the root,

The voices just can’t worm through.

If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two—-

The vampire who said he was you

And drank my blood for a year,

Seven years, if you want to know.

Daddy, you can lie back now.

There’s a stake in your fat black heart

And the villagers never liked you.

They are dancing and stamping on you.

They always knew it was you.

Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.

Sandra M. Gilbert’s essay on Plath, collected in the seminal study of women’s poetry, ‘Shakespeare’s Sisters’, is one of the first critical studies to define Plath primarily as a woman poet, powerfully arguing that she seeks a true female authorial voice through the restriction of the masculine, lyrical ‘I’. This can be seen in ‘Daddy’ as Ich, Ich, Ich, Ich. (German).

All the poems have a common preoccupation: the relation between the individual self and the process in which it comes to identity, to which it is always irreparably bound, and which sooner or later reclaims it. {Plath’s poetry goes beyond the polarised image of self and world, of the transcendent subject and immanent object, which characterises the poetry of most of her contemporaries. It is precisely, because her poetry is intensely private that it records so profoundly and distinctly the experience of living history.} In Plath’s poetry, there is no gap between private and public.

In a famous comment on one of her poems, ‘Daddy’, for the BBC Third programme, Plath spelt this out in explicitly Freudian terms:

‘The poem is spoken by a girl with an Electra Complex. Her father died while she thought he was God. Her case is complicated by the fact that her father was also a Nazi and her mother very possibly part Jewish. In the daughter, the two strains marry and paralyse each other, she has to act out the awful little allegory before she is free of it.

Though the daughter identifies with the ‘Jewish Mother, by the end of ‘Daddy’ she has become a phallic aggressor herself, rejoicing as ‘the villagers’ drive a stake through the fat black heart’ of the vampire father, cutting the black telephone off “at the root”, in an inescapable image of emasculation, so that “The voices just can’t worm through”. Cutting off the telephone means voices of the past out of which the self has been shaped.’

In that almost unnoticed progression from a single speaker to the collective image of the villagers, Plath gives a further twist to the revolt. She refuses the unitary self-imposed by the parental images, a unity always splitting into two opposed principles, of male and female, active and passive, Nazi and Jew.

The following lines suggest a female speaker whose latent desire for love and approval of her father is mixed with anger and resentment about his premature death:

“I was ten when they buried you.

At twenty I tried to die

And get back, back, back to you.”

The persona of the poem has even resurrected her father (symbolically) by marrying a kind of perverse surrogate father:

“I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf look

And love of the rack and screw.

And I said I do, I do.”

I have read these lines over and over and could not choose another poem from her collection as I feel this is the ultimate and appropriate to celebrate her birthday with her other poetry lovers.

References-

- The Poetry of Sylvia Plath- A Reader’s guide to essential criticism Ed. by Claire Breene- First ed. 2000 Icon Books Ltd.

- Suzanne Juhasz- Naked and Fiery Forms: Modern American Poetry by Women, a New Tradition. New York; Straus and Giroux, 1976.